On understanding the naval war

Avoid premature conclusions and underestimation of the challenges Ukraine is facing at sea.

The Kilo-class SSK Velikiy Novgorod in Sevastopol, August 2nd 2023. Source link

There has been an increase in not-particularly-good takes and hasty conclusions made on the naval war in the aftermath of recent Ukrainian strikes on Sevastopol. In the current discourse, there is a real potential for underestimating the Black Sea Fleet and the challenges Ukraine is facing at sea.

James Heappey is Minister of State (Minister for Armed Forces) at the UK Ministry of Defence. Link to original post

Ukraine has achieved a lot in the naval war, especially considering their limited resources compared to Russia so what I write in this article isn't downgrading their achievments. However, the Black Sea Fleet isn't “functionally defeated” (whatever that means), nor can one at the current time draw the conclusion that abandoned Sevastopol.

There is also a tendency to include the naval war into the equation when determining whether the Ukrainian offensive has been successful or not, something I think is wrong. I'm skeptical of labeling everything as "joint" or "multi domain operations".

As I see it, other services and domains sometimes plays a supporting role to the ground campaigns, other times they run what can be seen as their own wars. The evidence required to link operations together using such terminology in many cases simply isn't available.

Before returning to current events, a short look back is required as in order to understand the naval war, the timeline has to start at the beginning.

The phases of the naval war

To break down the naval war, I divide it into phases and we are currently in the fourth.

Phase 1 was from February 24th 2022 to the sinking of the Slava-class cruiser Moskva on April 13th/14th. In this phase until it abruptly ended, the Black Sea Fleet operated with impunity in the northwestern Black Sea.

Phase 2 went from the sinking of the Moskva until the Russians withdrew from Snake Island on June 30th. Despite the risks, the Black Sea Fleet continued to operate in the NW Black Sea, loosing the auxiliary Vasiliy Bekh in the process, until they eventually withdrew.

Phase 3 began in July 2022 and lasted until the grain deal expired on July 18th 2023. This period was characterized by increasing Ukrainian capabilities, especially in USVs, taking the fight to the Russians. The first major USV attack on Sevastopol was nearly a year ago, October 29th 2022. Since the start of this phase, except for patrol boats off NW Crimea, Russian warships have not operated in the NW Black Sea.

We are currently in Phase 4, which began with the end of the Grain Deal. This period has been characterized by some notable USV attacks, strikes on Sevastopol and a resumption of merchant traffic to ports in the Odessa area along with Russian strikes on Ukrainian ports.

A good, quick reference on the timeline of the naval war is maintained by HI Sutton.

What can one read from this?

The current status of the naval war is the result of a long-running, largely independent Ukrainian naval effort that kicked off in ernest with the sinking of the Moskva. This effort has evolved over time with increasing Ukrainian maritime capabilities, especially in USVs, and the use of Storm Shadow against Sevastopol. That this naval effort began so early in the war is the primary reason why I think connecting it to the counter offensive is wrong. What we see now is the result of decisions made long ago.

What has influenced Black Sea Fleet operations the most isn't the USVs but the threat from Ukrainian shore based anti-ship missiles. It is this threat that keep the Russians out of the NW Black Sea since July 2022 and also currently restricts Russias ability to enforce a blockade

Except for cruise missile strikes, Russian naval operations since July 2022 have mainly been reactive, responding too and defending against Ukrainian actions. Ukraine, despite being the underdog, holds the initiative and the Russians seems unable to reclaim it. Leadership and systemic issues have likely contributed to the Russian voes.

While the Black Sea Fleet has suffered painful and sometimes humiliating losses, their combat capability, especially when it comes to anti-surface warfare which also includes Naval Aviation and coastal missile units, hasn't been radically reduced. If the political decision to go after neutral merchant ships kinetically is made in Moscow, Ukraine will be hard pressed to reverse the situation and lift such a blockade.

The impact of the strikes on Sevastopol

WSJ headline October 4th, link to article (paywall)

In the aftermath of the strikes it has become a popular belief that Black Sea Fleet ships are vacating or being forced away from Sevastopol but I think it's too early to draw such a conclusion.

There has been an ebb and flow between Sevastopol and other bases the whole war, especially after Ukrainian attacks. One must have in mind that ships are most vulnerable in or near their bases to both USVs and long-range strikes, so some dispersal immediately afterwards is natural and expected. Missions and tasks of each ship vary over time, resulting in movement between bases.

In the past, deployments have returned to normal some time after a Ukrainian strikes against Sevastopol and this may happen this time too.

We have to wait and see before concluding.

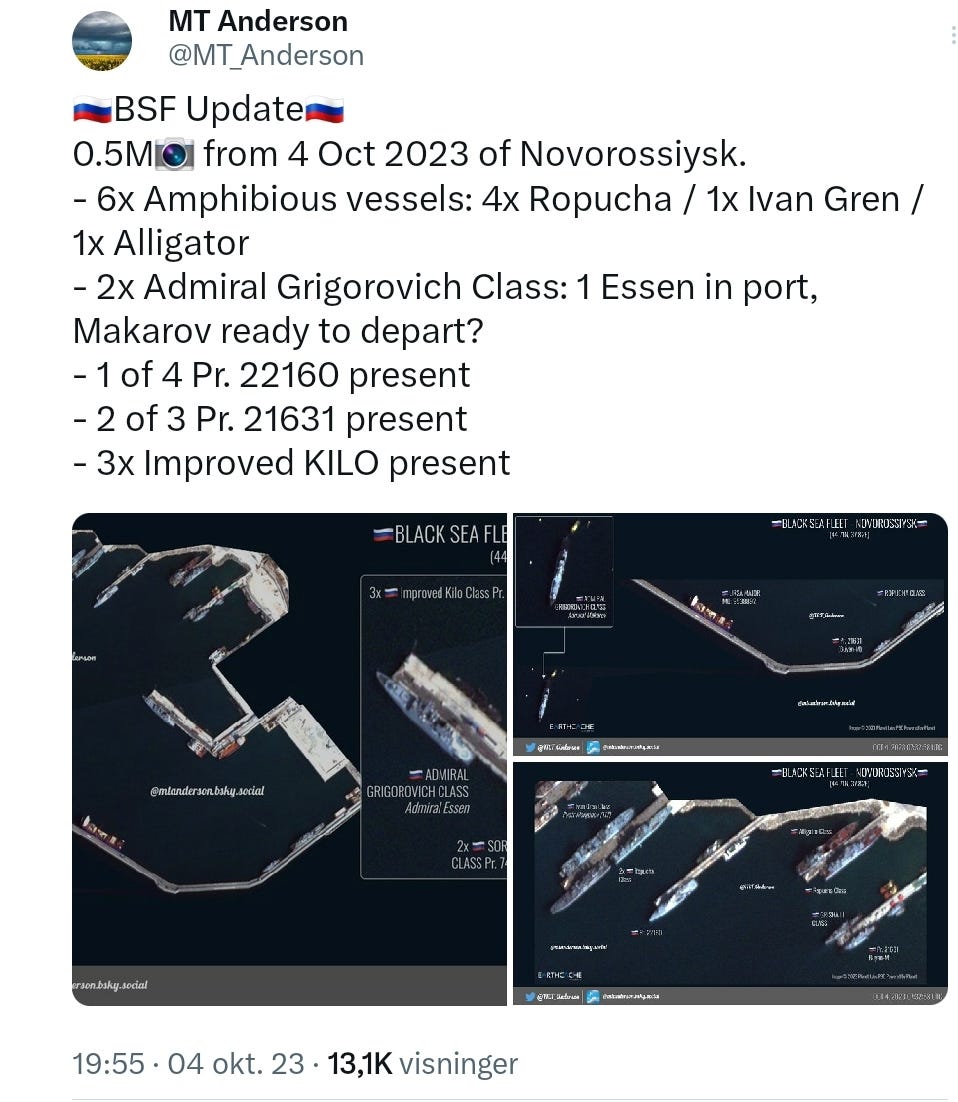

The majority of Kalibr shooters (Kilo-class SSKs, the Grigorovich-class FFGs and the Buyan-M corvettes) are currently in other bases than Sevastopol. Even if this type of deployment becomes permanent, a conclusion it's way too early to make, it will not have a significant impact in their operations.

The main task of these ships and the subs is launching cruise missile strikes and Kalibr has enough range to hit any target in Ukraine from anywhere on the Russian Black Sea Coast. Because of this aspect, I find the basing of Kalibr shooters to be a poor indicator of the Black Sea Fleet leaving Sevastopol.

As can be seen on the imagery on the post above, Sevastopol wasn't empty on October 2nd. Ships alongside there includes limited assets such as two AGIs, the submarine rescue ship Kommuna and a Kilo-class SSK.

Maintenance infrastructure in Sevastopol

The Storm Shadow strike on September 13th that put the Kilo-class SSK Rostov-na-Donu and the Ropucha-class LST Minsk out of commission, with the wrecks now occupying limited dry dock capacity, demonstrated something important.

The maintenance infrastructure in Sevastopol is the critical vulnerability of the Black Sea Fleet. Sevastopol's capabilities is not replacable elsewhere on a resonable timeline and Ukraine has shown they hit it.

However, it's too early to conclude on how big an impact on maintenance this strike will have and more importantly, there has been no Ukrainian follow-up strikes on similar targets. When it comes to strike campaigns in large wars of long duration, the enemy will recover from the consequences of a single strike, repair the damage and adapt.

To get real effects, pressure must be maintained over time and that means follow-up strikes.

Outlook for autumn and winter

The autumn and winter will likely see an increase in Ukrainian USV operations against naval bases, shore infrastructure including the Kerch Bridge and against warships and transports to Syria at sea.

There are no easy options for Russia to counter these operations but we will likely see increased shore-based defences and patrols by aircraft, helicopters, warships and patrol boats. This will require a heightened op-tempo from the Fleet and FSB Coast Guard and could stretch their resources.

The weather will likely impact USV operations, especially the long range strikes, so we could see an ebb and flow depending on meteorological conditions.

In addition to this, from my earlier Autumn Approaches: Part 3 , and despite no follow-up strikes against Sevastopol maintenance facilities far, I do think future Ukrainian strikes on Navy related infrastructure is likely.

Frequency and intensity will be dependent on missile availability. Storm Shadow/SCALP and Neptune numbers are limited and there are other targeting priorities too. Ukrainian UAV capabilities are also increasing so there's a real possibility of these being used against Navy related targets but in general, UAVs are much less effective than cruise missiles.

The Black Sea Fleet appears to be very risk averse compared to other parts of the Russian military but I think that is because their assigned missions doesn't require them to take excessive risks. Future events may change that so I would caution against making the conclusion that the Fleet always will run away when pressured.

Civilian traffic to ports in the Odessa area

Under a scheme initiated by Ukraine, merchant traffic has resumed to ports in the Odessa area and as mentioned earlier, Russian haven't been able to interdict this traffic so far

According to exit266 on Twitter/X, who does a very good job tracking merchant traffic and related activities in the Black Sea, tonnage to/from the Odessa area is now approaching that of the last months of the Grain Deal, when Russia was dragging out inspections and refusing ships, but is still well below what was achieved between August 2022 and April 2023.

On the other end, any incidents or deliberate Russian actions can rapidly restrict or halt traffic and as mentioned above, if Russian starts hitting neutral merchant ships, Ukraine will be hard pressed to reverse the situation.

The main reason why Russia haven't gone down this road is political. Striking neutral shipping now would be a severe escalation, with a real risk of dragging other countries more directly into the war. This is something Russia so far has wanted to avoid. There is also a risk such actions could trigger Ukrainian retaliation against shipping going to Russian ports. Due to the risks unrestricted naval warfare brings with it, one can say Russia so far has been deterred from unleashing it and this keeps Ukrainian ports open

Any traffic to and from Ukrainian ports is a good thing and resumption of traffic has gone better, delivering more tonnage than I originally thought possible. I do hope this traffic can be sustained and increased while we avoid a decent into unrestricted warfare. However, if the political decision is made, Russia retains the capabilities to halt traffic and will likely have this capability for foreseeable future.

Summing up

What prompted me to write this article was the trend of overestimating effects and jumping to conclusions on the current status of the naval war.

The current situation has developed over time and new developments must be viewed in this context, not as new, independent events. I would also caution against looking at everything through the lense of the counter-offensive, as important developments in the naval war happened back in 2022 and key Ukrainian efforts were started long before the offensive was conceived.

Of Ukrainian sea denial capabilities, what influences Black Sea Fleet operations the most is shore based missiles and this has been the case for over a year.

On deployments away from Sevastopol, it's too early to draw hard conclusions. Going by past events, it is likely we will see Kalibr shooters and submarines in Sevastopol again at some point in time. For certain types of maintenance, there are no alternatives but Sevastopol.

It is very understandable that Ukraine wants to highlight their successes and paint the Black Sea Fleet as weak. The role of analysts and the media though is to look through this, study known facts while acknowledging uncertainty and provide the right context when explaining events and what they mean.

By jumping on tabloid conclusions, there is a real risk of overestimating the impact of Ukrainian actions, underestimating the Black Sea Fleet, resulting in a wrong understanding of the challenges Ukraine is facing at sea.

Ukraine currently holds the initiative at sea, no small feat, but there is a long war still ahead of us.

Regards

Thord Are Iversen

Great post, really enjoyed reading it.